During the final year (2007-08) of my Physics degree at Imperial College, we studied a module called Research Interfaces (RI). This was a team-based module that focussed on transforming scientific research into commercial business propositions.

This was a highlight of the degree for me: I loved the collaborative nature of it and the entrepreneurial challenge was much more aligned with how I wanted to live my future life.

Our product design: MirrorMirror

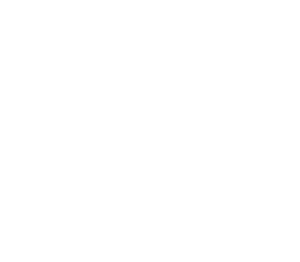

Our team designed a product with the working name of MirrorMirror. It was a booth containing a network of cameras with a central computer that would stitch together the images to create a 3D scan model of the user’s body.

This would then be used to generate an avatar that would help them choose clothes that fit and suit them perfectly when shopping online.

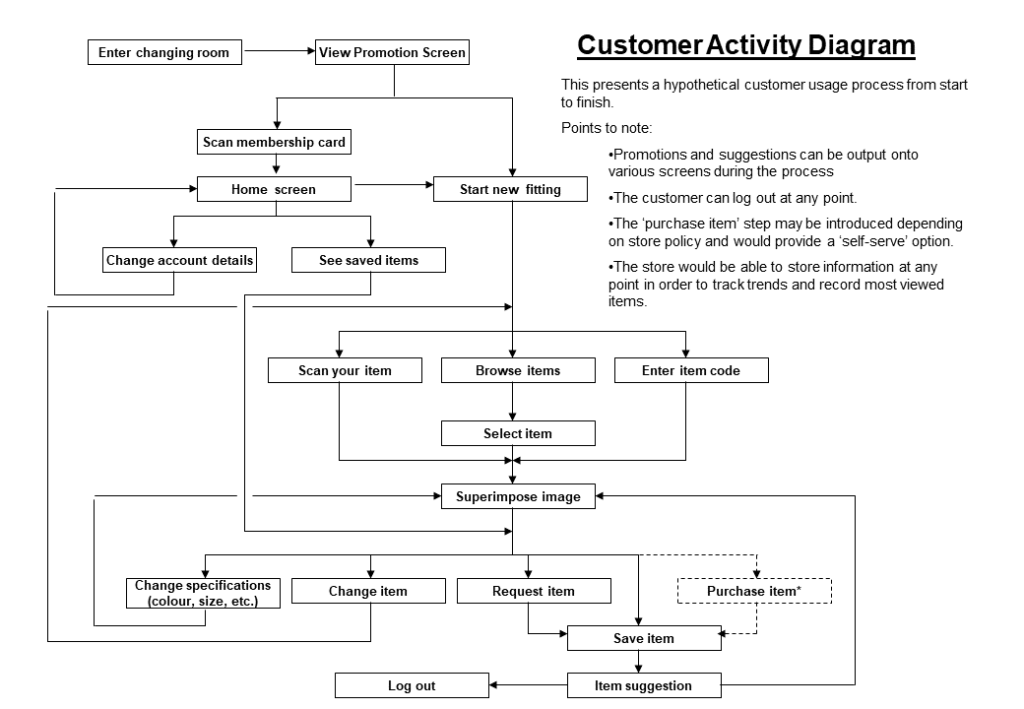

Additionally, they could see their body on a screen in real time with different clothing options projected over the image as if they were wearing it (so-called “Augmented Reality”). This reminded us of the magic mirror from the Disney film, Snow White (hence the name MirrorMirror).

There could also be other uses like tracking weight loss for dieters and muscle gain for bodybuilders (if a new scan was made regularly to show the incremental changes) or the visualisation of the results of cosmetic surgery.

Technical Design

We produced several outputs for the class including this Technical Design Review.

In that document, we estimated the cost to build the prototype of £1.45m, a total future manufacturing cost per booth of £13,900, and a price point of £50,000.

This is exceptionally high and I believe it is a result of the fact that we were not actually required by the course to do any prototyping work. If we had, I think we would have focused on looking for a cheaper way to execute the plan.

Our original design required a screen behind a half-silvered mirror. I think in 2018 this would not be required as screens are not of incredible quality and image processing technology has come on exponentially in the last decade.

User experience

We believed that there are many high-end lucrative markets (such as wedding dresses, evening wear and saris) where a quicker and less stressful garment trial process would greatly add to the shopping experience.

Our team also saw the potential for future uses such as generating an accurate avatar of the person that can be used as a little virtual model for the clothes that are being selected. Imagine being email a picture of yourself wearing the latest items from your favourite designer and a link to buy exactly the right size for you?

We envisioned that booths could be installed in shopping centres, allowing customers to create a 3D image of themselves which they could then use to shop online. Additional lucrative applications could also include high-fashion hairdressing.

Our plan of the user journey is mapped in the image below:

Business Case and Financial Model

You can see the basic financial model we generated here: MirrorMirror Costing.

When I say we, it was actually me that had the responsibility for putting it together and I could have circulated the draft to my team-mates before the deadline so we could have had more eyes on it before submission. We got our lowest grade by far for this part of the module, so I did feel a bit guilty! However, it was apparently the same for all the other teams, so my guilt was slightly assuaged.

After 10 years working in and around startups and scaleups, here are what I see as the big errors and omissions:

- No time series for the values (everything is static)

- Lag time between initial burn and revenue

- A proper cash-flow model would have helped clarify this

- Significant errors on the business model (i.e. how we could get paid)

- For example, would we really want to make money on the hardware, or would we prefer to make money on the service provided by the software (i.e. charge money for every image processed – a digital version of the Nespresso model)

- No R&D tax credits, Government grants, or other potential subsidies included

- No marketing and sales budget included at all!

It is quite satisfying to look at old work such as this and compare it with what I have learned since then!

Final Pitch

At the end of the 3-month module, we had to deliver a pitch to a packed auditorium and a simulated panel of investors (made up by the professors from the Business and Physics department that ran the course).

You can see our final pitch document here.

This was a really enjoyable part of the course. I delivered it with 2 other teammates and we got everyone in the team up on stage for the Q&A at the end.

Outcome

We actually won the Elevator Pitch Prize at the end of the module which was a very personally satisfying way to end the project. We all received a good first for the course (>85%) which was very satisfying for all of us.

We entered into the wider university’s Business Challenge entrepreneurship competition, but we didn’t get past the initial screening phase. As a result, we all agreed to disband the project outside of the RI module and did not take it any further.

What didn’t we do?

It is quite telling that we didn’t build a prototype!!!

The reason that we didn’t build anything is that we didn’t have anyone that is super-focused on the tech side i.e. that could be a CTO. I also believe it is because we all saw this as a purely academic exercise and not as a true opportunity to start an entrepreneurial endeavour and make a return with it.

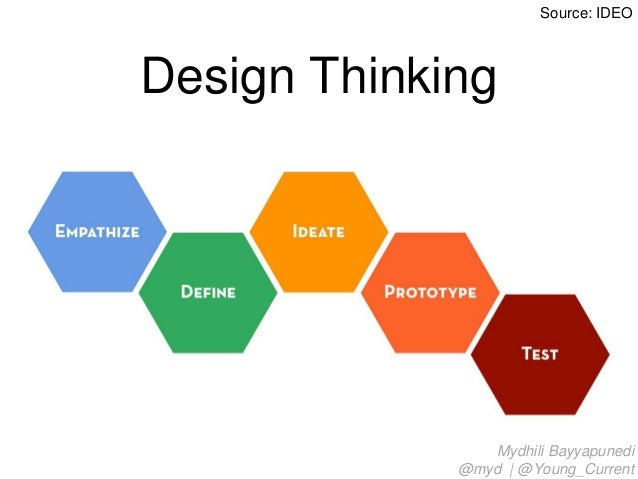

This tinkering on a prototype would have actually helped us see the true costs, challenges around manufacturing, and gaps in the business model. In fact, IDEO’s Design Thinking methodology (diagram below) expressly integrates prototyping as part of the design process. This project was perfect evidence of why that is the case.

I wonder if the Blackett lab requires the students on the RI course to build a prototype as part of the course nowadays?